The Shifting Sands of Self: How We Define Ourselves in Relation to Others

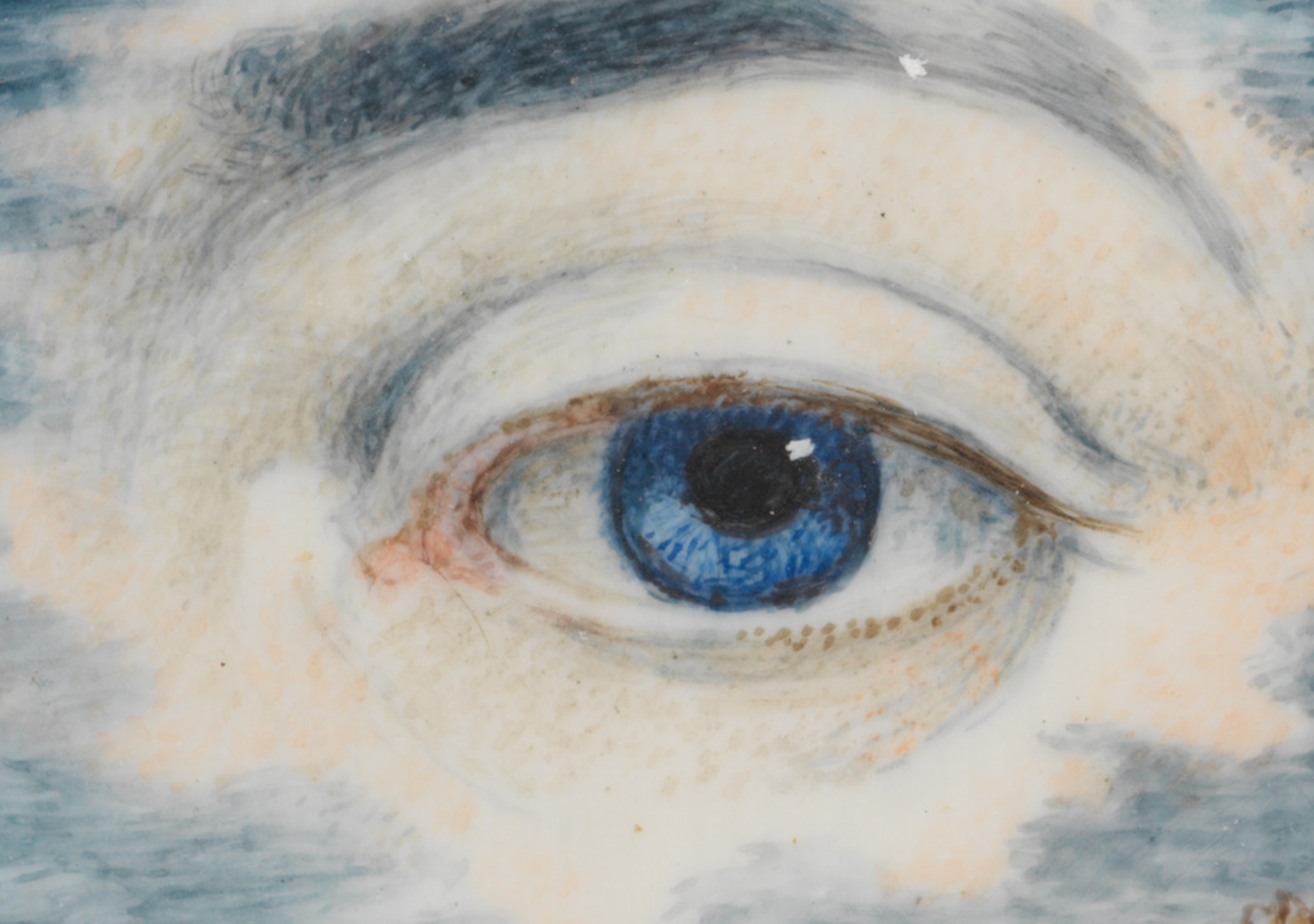

Image: Lover’s Eye Locket c. 1840 The Met Museum (public domain)

The Problem of Definition

Defining self is surprisingly complex. We intuitively know what we mean when we say “I,” but articulating a clear, objective definition proves elusive. A core difficulty lies in our reliance on external references (the other) to understand ourselves.

The “other” isn’t simply other people, though that’s certainly a significant component. It encompasses the entirety of the external world against which we define ourselves: culture, history, social groups, family, even strangers and political affiliations. These established definitions, structures, and expectations represent all that we know. Essentially, they are the framework society provides for understanding what is considered right, wrong, accurate or inaccurate. These frameworks are tools we use to evaluate ourselves.

We are defined by the other through roles, statuses, and associations. The adage “you can tell the character of a person by looking at who his friends are” highlights this principle. Meaning, in this context, is derived from how accurately we reflect and are accepted by these external references.

But what remains when we attempt to define the self without these external points of reference? It’s a challenging question because defining the self requires context. Without it, the “self” becomes an unbounded, limitless source, akin to a wave function in physics before it collapses into a measurable state. It’s a potentiality without form, lacking the vocabulary or context for self-understanding.

This leads to an important point: observation itself is a function of the other. While external observation allows for definition and context, it simultaneously alters what is being measured or evaluated. The “self” we assess isn’t the pure, unobserved self, but rather the self as given meaning by external context. This can be expressed as a simple equivalency: Actor/Observer = Self/Other. The other, acts as the observer, measurer, and validator of our sense of self.

Meaning

The relationship between self and other is fundamentally about meaning. If the problem of definition explains why the self is difficult to locate, the problem of meaning explains how we live with that difficulty.

Meaning derived from the other is defined, understood, and contextualized through acceptance, validation, and external mechanisms of control. Ideally, these mechanisms guide us toward positive outcomes. Over time, these external influences become internalized, forming what we recognize as our values and beliefs.

However, the meaning of the self is different. It remains an undefinable construct. Everyone feels as if they know what the self is, yet attempts to define it empirically are inherently problematic. The self is constantly changing, and any attempt to capture its meaning within a specific context is necessarily incomplete.

Consider a raindrop. In the sky, it’s a part of falling mist. On a window, it’s a smudge. In the ocean, it’s indistinguishable from the surrounding water. The self, like the raindrop, is a sense of continuity experienced through transformation. Labeling it in one context cannot capture its full meaning.

The “flow state," that feeling of complete immersion in an activity where time seems to disappear," offers a glimpse of this elusive self. In flow, actions become effortlessly linked to cognition, and emotion is no longer driven by simple stimulus-response. That “something else” driving the experience, whatever it is, might be the closest we come to experiencing the self directly.

The Loss of Self in Modern Society

Contemporary society often prioritizes contextualized meaning (meaning derived from external sources). Over time, this emphasis can lead to a subtle reversal: the other no longer provides context for the self, but increasingly becomes the self.

This shift is rarely experienced as coercion. More often, it feels like participation. Identity is affirmed through alignment with groups, narratives, and symbolic markers that signal belonging. The self learns which responses are rewarded and which are punished, and gradually adapts. What begins as social learning becomes a stimulus–response loop. Conformity is reinforced not because it is consciously chosen, but because deviation threatens the coherence of identity itself.

In this environment, disagreement is no longer simply disagreement. It is experienced as personal destabilization. A challenge to group norms feels like a challenge to the self, triggering familiar ego defenses: denial, rationalization, and projection. But now, these maladaptive ego defenses are operating at a collective level. The result is tribalism that is less about shared goals and more about self-preservation.

This dynamic is especially visible in modern digital spaces. Online identities are often constructed almost entirely through external validation; likes, shares, algorithmic reinforcement, and group approval. Expression of the self becomes performative, not exploratory. Over time, the individual may lose contact with the quieter, less defined aspects of self that exist outside these feedback loops. Identity becomes rigid, reactive, and fragile, maintained through constant signaling rather than organic transformation.

When meaning is derived almost exclusively from the other, autonomy erodes. The self is no longer changing through reflection and experience, but is being reshaped by external pressure. What remains may look like identity, but it functions more like a role; it is stable only as long as the surrounding context remains intact.

The Crossroads

The tension between self and other does not resolve itself. It must be navigated. Meaning does not reside fully in either pole, but emerges in the space between them.

When the other dominates, meaning hardens. Identity becomes fixed, monitored, and defended. Belonging is maintained through compliance, and deviation is experienced as threat. In this state, the self is preserved by resisting change rather than engaging with it.

When the self dominates, meaning dissolves. Experience becomes private and unanchored, untethered from shared language or responsibility. Insight may feel profound, but without context it cannot be communicated, tested, or integrated into lived life.

The crossroads is not a midpoint between these extremes, but an ongoing stance of awareness. The self is not a static entity to be protected, nor a blank slate to be filled. It is a continuity experienced through change; one that exists independently of external validation, yet requires context in order to take form.

The other remains essential. It provides language, structure, and shared reference points. But it is no longer mistaken for the source of meaning itself. Likewise, the self is acknowledged as real and persistent, but not as an isolated authority divorced from consequence or connection.

Meaning, then, is not discovered once and for all. It is continually negotiated through reflection, engagement, and restraint. In recognizing this, the self regains a measure of autonomy. This is accomplished not by rejecting the world, but by standing within it without being wholly defined by it.

Related Content on The Wiki:

About the Author

Rod Price has spent his career in human services, supporting mental health and addiction recovery, and teaching courses on human behavior. A lifelong seeker of meaning through music, reflection, and quiet insight, he created Quiet Frontier as a space for thoughtful conversation in a noisy world.